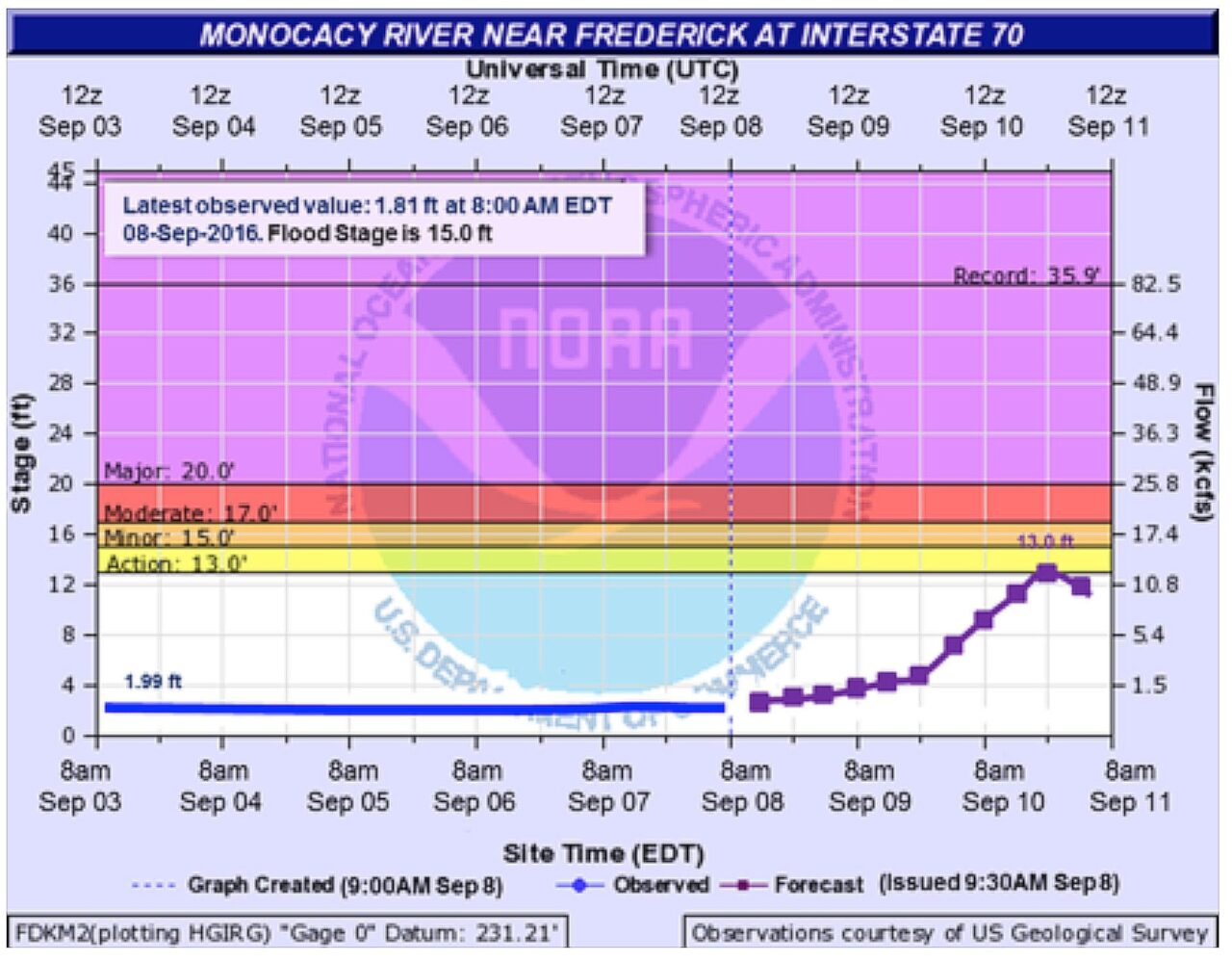

What do these all really mean? When we want to understand how high our rivers and creeks are likely to rise in the future, or when we think about daily weather forecasts, we often think in thin straight lines – deterministic forecasts that tell us exactly what to expect, and when. For instance, the hydrograph, beloved by river residents, forecasts the time and height of the river up to 5 days in advance. Or our local weather offices let us know to expect an inch of rain tomorrow afternoon.

But we know it isn’t always so straightforward. Meteorological (weather) forecasts can influence hydrologic (in this case, river) outcomes dramatically. If a storm tracks, say, west or south more than expected, the river levels could be much different than anticipated. The accuracy for deterministic forecasts is quite high, but increased accuracy of longer-range models is allowing forecasters to represent the inherent uncertainty in river forecasts, and to produce a more detailed representation of the range of possible outcomes. These forecasts rely on an ensemble of models (models run multiple ways multiple times) to reflect the actual range of possible river level outcomes. These forecasts represent the probability that the river will reach certain levels. With this information, emergency managers, water resource managers and residents can better understand the possible outcomes, and can use this information for planning and decision-making about when and whether to take action, and what kinds of actions.

But giving probabilistic information clearly isn’t easy, and sometimes, can be more confusing than helpful. This challenge – communicating risk and uncertainty – is what NNC and its research partner East Carolina University tackled in its most recent research study, “Major Risks, Uncertain Outcomes: Making Ensemble Forecasts Work for Multiple Audiences.” This study, funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) looked at the emerging capacity of the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Hydrologic Ensemble Forecasting System (HEFS), a national system that provides short and long-range forecasts ranging from 6 hours to 1 year.

HEFS holds promise for providing more and better information about the possible levels for rivers and creeks at thousands of points across the country. The challenge is to present this information in a way that allows users to make sense of the information shown and inform their decision-making.

To help with this issue, NNC and ECU hosted focus groups in 2016 with residents, emergency managers and water resource managers in West Virginia and Maryland to explore how they understand, currently use and might in the future use the various HEFS products. Using risk communication and graphic design principles and user feedback, the research team made a series of revisions to the products and rested them with a new group of users in those same communities in 2017.

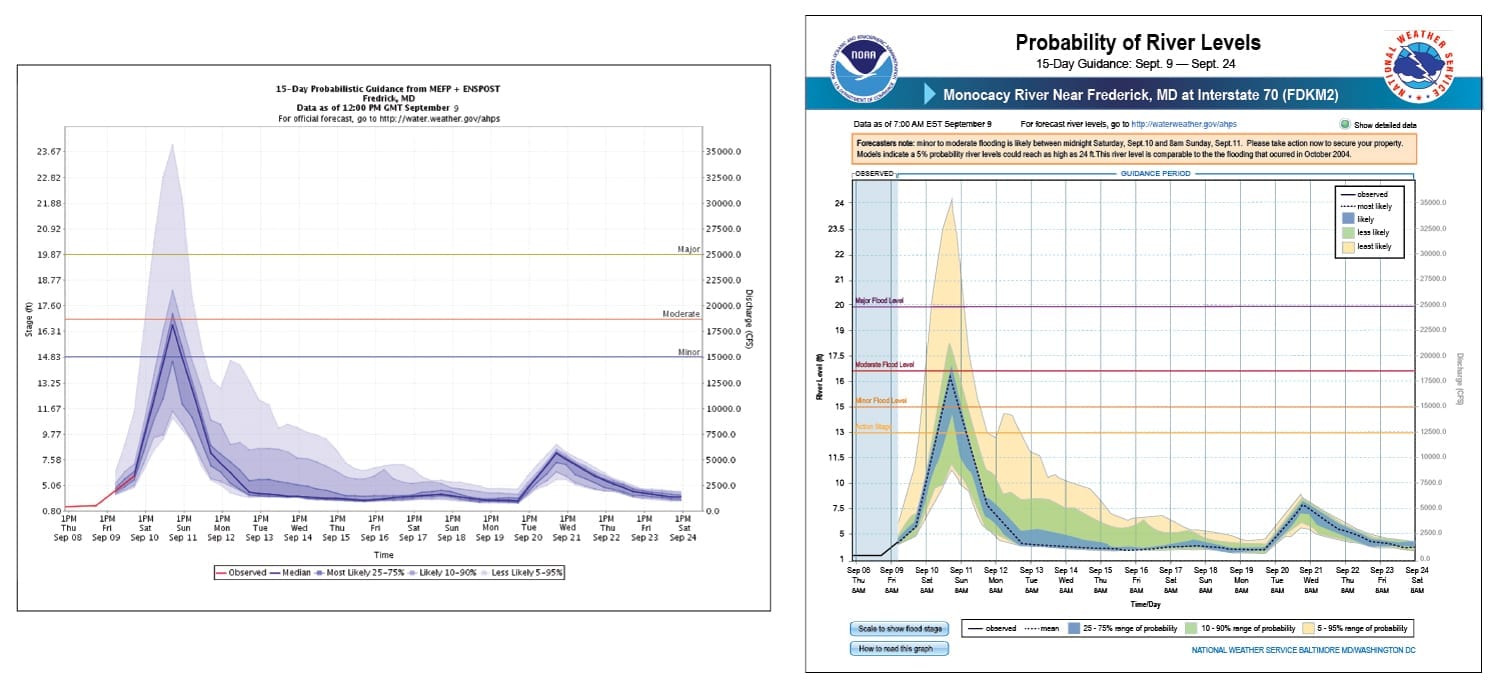

What did we find? For professional users, more information on uncertainty was helpful. Though the products forecasted 15 days in the future, emergency managers generally said they would use them for planning only 7 days out, and as part of a suite of other information sources. Water resource managers were eager for longer-term probabilistic forecasts to use in managing large water systems. But residents often felt overwhelmed by the information. Even when design changes removed some of the challenges to understanding the products, residents still did not prefer the probabilistic forecasts. The research team’s final report, issued earlier in 2018, includes a series of recommendations for ways the products can be improved, including changes to the legend, use of color, text, and overall graphic representation, as well as considerations about whether one product can meet the needs of such varied users. NWS is now working to integrate the recommendations into operations.

Figure 2. 15-Day Probabilistic Guidance as tested initially (left) and after research team revisions (right).

This project is one step in an ongoing process by many in the larger weather community to understand user needs for weather and river forecasting. Technology advances have improved forecast accuracy tremendously. Now the challenge is to learn how to properly communicate risks and uncertainty so users can be better informed and make decisions to protect life and property. To see the full report, including all recommendations from the research team, click here.